The Settlement of Kurd-Dagh until the Ottomans

A Diachronic Analysis

Introduction: The Landscape and its Deep History

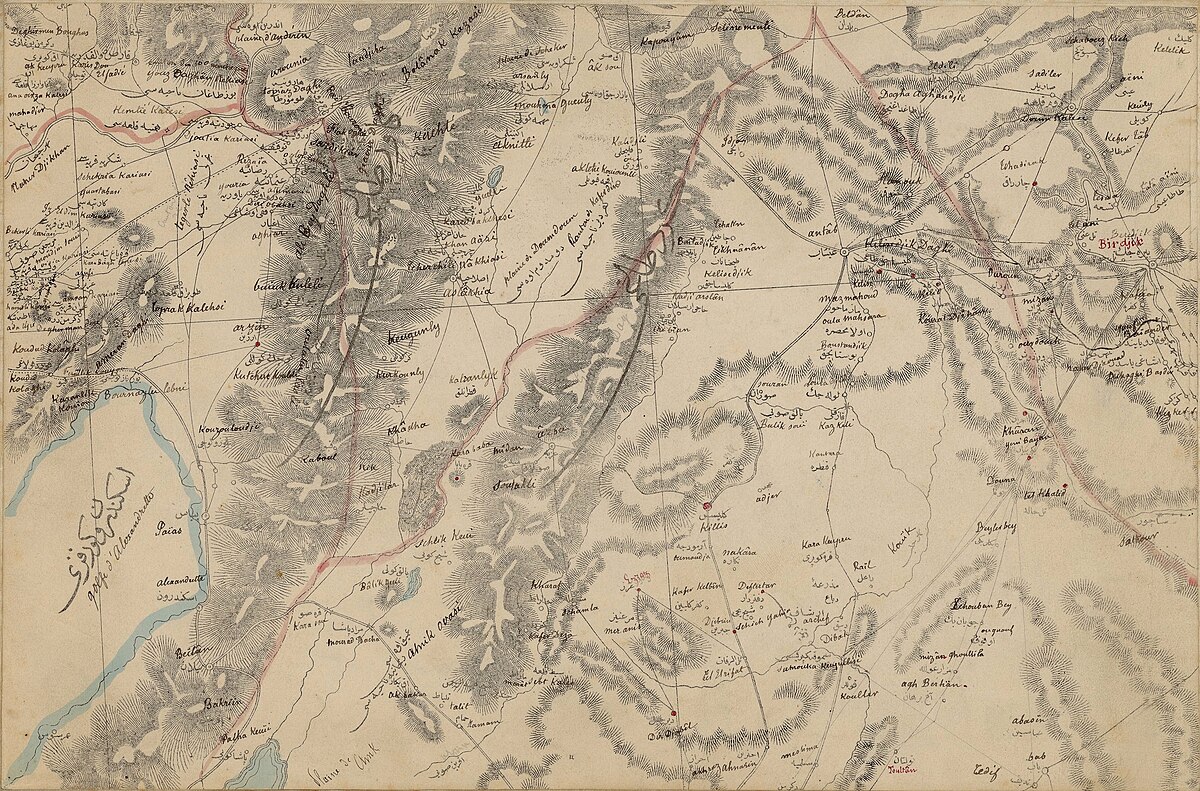

The Afrin region of northwestern Syria, historically and geographically centered on the Afrin River valley and the surrounding highlands of Kurd-Dagh (Mountain of the Kurds), represents a critical nexus of civilizations, a landscape shaped by millennia of settlement, conflict, and cultivation. To understand the establishment of its villages is to trace the diachronic interplay of geography, imperial strategy, economic imperatives, and ethno-tribal movements. This report provides a comprehensive analysis of the specific historical periods that saw the creation of rural settlements in this region and the complex factors that drove their foundation, covering the vast expanse of time from the earliest evidence of habitation to the eve of the French Mandate in the early 20th century. By examining each era—from the Neolithic through the Classical, Islamic, and Mamluk periods—this analysis moves beyond a singular focus on any one epoch to reveal a multi-layered history of settlement, demonstrating how enduring environmental factors interacted with shifting political and social structures to create the region's distinctive rural tapestry.

Geographical and Ecological Context

The Afrin region is defined by two dominant geographical features: the fertile alluvial plain of the Afrin River and the limestone highlands of the Kurd-Dagh. [1] Geologically, Kurd-Dagh is a southern continuation of the Aintab plateau and part of the extensive Limestone Massif of northwestern Syria. [1] This strategic location has historically positioned it as a crucial corridor and a natural frontier. It serves as a gateway between the Anatolian plateau to the north and the vast Syrian plains to the east, while the Afrin River valley provides a pathway south towards the Amuq Valley and the Mediterranean coast near Antioch. [2] This function as a crossroads is a fundamental and recurring theme throughout its history, making it a coveted and contested territory for successive empires.

The region's ecology has been a primary determinant of its settlement patterns. The limestone hills, while rugged, are exceptionally well-suited for the cultivation of olives, an agricultural staple that has defined the local economy for millennia. [1] Indeed, Syria is widely considered to be the cradle of olive cultivation, with a history of its use stretching back to approximately 2400 BCE. [4] The Afrin River, known in antiquity as the

Oinoparas and later the Ufrenus , along with its tributaries and numerous springs, provides the vital water resources necessary for sustaining both agriculture and concentrated human settlement in this semi-arid environment. [5] The combination of defensible highlands and a fertile, well-watered valley created an ideal landscape for the development of a resilient, agriculture-based society.

Thesis and Approach

The establishment of villages in the Afrin region was not a monolithic event but a cumulative, diachronic process driven by a shifting matrix of influences. This report argues that the region's settlement history is best understood as a product of the continuous interaction between four primary forces: the imperatives of imperial strategic control, the opportunities of regional agricultural economies, the implementation of specific administrative and land tenure systems, and the complex dynamics of ethno-tribal settlement, particularly that of Kurdish groups. By adopting a chronological framework that begins with the earliest archaeological evidence and progresses through the Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, and various Islamic periods, this analysis will demonstrate how the relative importance of these factors changed over time. It will show that while the fundamental geographic advantages of the region provided a constant impetus for settlement, the character, density, and social organization of its villages were repeatedly reshaped by the political and economic superstructures imposed by dominant regional powers.

Foundations of Settlement: From the Neolithic to the Iron Age

The history of village life in the Afrin region is deeply rooted, extending back to the very dawn of sedentary civilization in the Fertile Crescent. Long before the area was drawn into the orbit of great empires, its fertile valleys and defensible hills nurtured early agricultural communities. Archaeological evidence reveals a pattern of continuous human habitation, culminating in the Iron Age with the rise of complex regional centers that presuppose a well-established network of supporting rural settlements. This foundational period demonstrates that the region's intrinsic environmental advantages were the primary drivers for the initial establishment of villages.

Early Agricultural Communities (Neolithic-Chalcolithic, c. 6000-3000 BCE)

The Afrin region has seen human settlement since the early Neolithic period, marking it as one of the ancient landscapes where the transition from nomadic hunting and gathering to settled agriculture took place. [3] The archaeological site of Ain Dara, located just south of the modern town of Afrin, shows its earliest signs of habitation in the Chalcolithic, or Copper Age, during the fourth millennium BCE. [9] The establishment of these primordial villages was driven by the same fundamental factors that spurred the "urban revolution" across the Near East: the presence of fertile soil in river basins and reliable access to water. [6] The Afrin River and its tributaries provided the necessary hydrography for nascent agriculture, allowing for the cultivation of crops and the husbandry of animals, which in turn enabled the formation of permanent, sedentary communities. [6] These early settlements were likely small, unorganized clusters of dwellings, their locations dictated purely by proximity to life-sustaining resources. [6]

The Rise of Regional Centers (Bronze and Iron Ages, c. 3000-333 BCE)

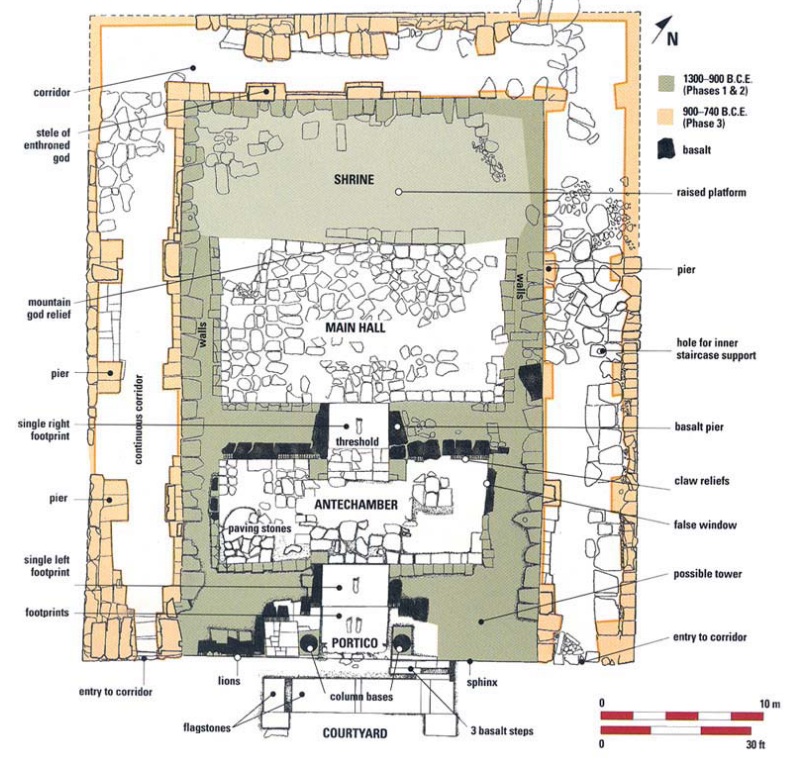

By the Iron Age (c. 1200-539 BCE), the settlement landscape of northern Syria had evolved significantly. The region became home to a number of powerful Syro-Hittite (also referred to as Luwian or Aramean) city-states and principalities. [12] The most prominent evidence for this level of social and political organization within the Afrin valley is the temple complex at Ain Dara. Flourishing between approximately 1300 BCE and 740 BCE, Ain Dara was a major religious and administrative center, not merely an isolated shrine. [5]

The site's layout, covering 25 hectares and comprising a fortified Upper City (acropolis) on a high tell and an extensive Lower Town, is indicative of a sophisticated, hierarchical society. [9] The construction of its monumental temple, with its intricate basalt reliefs, colossal carved footprints representing a striding deity, and architectural parallels to the biblical Solomon's Temple, would have been a massive undertaking. [9] Such a project necessitates a stable and prosperous society with a significant agricultural surplus, which could only have been generated by a network of subordinate villages in the surrounding valley. These rural settlements would have provided the food, resources, and labor required to sustain the priests, artisans, soldiers, and administrators residing in the central town. The discovery of a 9th or 8th century BCE Luwian stele in a field near Afrin further cements the region's integration into this cultural and political sphere, confirming that it was not a remote backwater but an active part of the Syro-Anatolian world. [5] During this era, the primary factor in village location expanded beyond mere subsistence to include its role within a regional political and economic hierarchy, serving a central administrative hub like Ain Dara.

The remarkable continuity of settlement at sites like Ain Dara, which remained occupied from the Chalcolithic period through multiple empires until the Ottoman era, points to a powerful underlying logic in the region's human geography. [9] This longevity, spanning millennia of profound political and cultural upheaval—including the Bronze Age collapse, the Assyrian and Babylonian conquests, and the subsequent arrivals of Persians, Greeks, and Romans—suggests that the core geographical and agricultural advantages of the Afrin Valley were so profound as to be determinative. [5] While the ruling elites and the ethnic composition of the inhabitants may have changed, the viability of the locations for settled life remained constant. This implies that the "village" as a mode of social and economic organization was the enduring feature of the landscape. Many of the villages that existed in later historical periods may well have had their origins in these ancient settlements, their foundations laid upon sites chosen for their timeless advantages of water, fertile land, and strategic position. The political superstructure was the variable; the agricultural village was the constant.

The Classical Apex: Imperial Control and Agricultural Prosperity (c. 333 BCE – 637 CE)

The arrival of Hellenistic and, subsequently, Roman power in the Near East marked a transformative era for the Afrin region. During this long period of imperial consolidation, the factors driving the establishment and growth of villages evolved from local subsistence and regional hierarchies to integration within a vast, interconnected imperial system. Rural settlement patterns were profoundly shaped by two dominant forces: the strategic military imperatives of the Seleucid and Roman empires, which established major bases in the region, and the development of a highly profitable, export-oriented agricultural economy based on olive oil production. This era likely witnessed a significant increase in population density and the number of rural settlements, representing an apex of prosperity that would not be seen again until the modern period. It is also within this context of imperial strategy that the first plausible, though debated, evidence for a Kurdish presence in the region emerges.

Hellenistic and Roman Strategic Imperatives

Following the conquests of Alexander the Great, the Afrin region was absorbed into the Seleucid Empire (312-63 BCE). [5] It became part of a district known as Cyrrhestica, named after its administrative and military center, Cyrrhus (the modern site of Nabi Huri), which was strategically situated on a hill overlooking the Afrin Valley. [3] During this period, the Afrin River was known by its Koine Greek name,

Oinoparas . [5] The establishment of Cyrrhus as a major regional center would have spurred the growth of villages in its hinterland to provide supplies and labor.

The Roman annexation of Syria in 64 BCE intensified this trend. The region was incorporated into the Roman province of Syria , and later, after the provincial reorganization under Septimius Severus in 193 CE, into Coele Syria . [3] The Romans recognized the strategic value of Cyrrhus and expanded it into a formidable military base, garrisoning legions there for campaigns against the Parthian Empire to the east and the Kingdom of Armenia to the north. [5] The river's name was Latinized to

Ufrenus , which is the direct etymological ancestor of the modern name "Afrin". [5] The logistical needs of a large and permanent Roman military presence—including food, fodder, leather, and other materials—would have created a massive, stable, and monetized local market. This demand was a powerful engine for the establishment and expansion of agricultural villages throughout the valley, whose primary economic function would have been to act as suppliers for the Roman state apparatus. By the 4th century CE, Cyrrhus had also become an important center for Christianity, with its own bishop, indicating a substantial and settled civilian population alongside the military garrison. [5]

The Olive Oil Boom and the "Dead Cities"

Beyond its military importance, the Afrin region during the Late Roman and Byzantine periods (c. 4th-7th centuries CE) participated in a remarkable economic boom that transformed the rural landscape of northwestern Syria. This prosperity is most famously attested by the hundreds of well-preserved abandoned settlements in the Limestone Massif, often referred to as the "Dead Cities". [17] These were not cities in the modern sense, but rather a dense network of prosperous agricultural towns and villages. Their wealth was built almost exclusively on the cultivation of olives and the industrial-scale production of olive oil for export. [19] This lucrative trade supplied the great metropolises of the Eastern Mediterranean, such as Antioch and Apamea, and was a key component of the Roman imperial economy. [19]

The archaeological remains of the "Dead Cities" reveal a highly organized and sophisticated agricultural society. The landscape was systematically managed, with evidence of Roman agricultural plot plans, protective stone walls enclosing fields, and advanced hydraulic engineering, including numerous cisterns for water storage and elaborate stone presses for oil extraction. [18] The Kurd-Dagh, being geographically and geologically an integral part of this same Limestone Massif, almost certainly shared in this economic flourishing. [1] The factors that enabled the prosperity of the "Dead Cities"—a stable political environment under the

Pax Romana , secure trade routes, and a massive market for olive oil—were regional in scope. Therefore, the establishment and growth of villages in the Afrin region during this period were likely not driven by subsistence farming but by their integration into a highly profitable, monetized, and export-oriented agricultural industry. This economic boom would have supported a far greater population density than in previous eras, fueling the foundation of new villages and the expansion of existing ones. This period represents a fundamental shift, reframing the narrative of Afrin's villages from one of simple farming to one of commercial agribusiness, deeply embedded within the economic fabric of the Roman Empire.

Early Evidence of Kurdish Presence

It is within the strategic context of the Hellenistic and Roman periods that some scholars place the earliest settlement of Kurds in the region. Stefan Sperl posits that Kurdish groups may have been settled in the Kurd Mountains as early as the Seleucid era. [3] According to this hypothesis, they served as mercenaries and skilled mounted archers, placed strategically along the vital route connecting the Anatolian highlands to the Seleucid capital of Antioch. This practice would align with the well-documented use of Kurds as soldiers by various empires throughout history. [20]

This hypothesis finds a compelling parallel in the broader Roman and Byzantine strategy of frontier defense. The empires often secured their borders, such as the Limes Arabicus in the south and east, not just with forts but by settling allied tribal groups, known as foederati , to act as a buffer and a first line of defense against external threats. [22] These groups were granted land and subsidies in exchange for military service. While the Kurd-Dagh was not part of the formal

Limes Arabicus , it was a critical frontier zone controlling a strategic highland pass. The settlement of a loyal and martial people like the Kurds in this area would have been a logical application of established imperial statecraft. Such a policy would mean that some of the region's villages may not have emerged organically from agricultural expansion but were deliberately founded as military colonies, their inhabitants owing service to the state. While direct archaeological proof for this specific period remains elusive, it is historically recorded that by the time of the Crusades in the late 11th century, the Kurd Mountains were already considered to be Kurdish-inhabited, indicating a long and well-established presence before that time. [3]

Imperial Strategy

Military Engine

The establishment of Roman Cyrrhus created a massive local market, fueling village growth to supply the legions.

Agricultural Boom

Liquid Gold

Villages became centers for industrial-scale olive oil production for export across the Roman Empire.

Kurdish Foederati

Frontier Defense

Kurdish tribes may have been settled as allied military colonies (foederati) to guard strategic routes.

The Medieval Transition: Shifting Caliphates and Contested Frontiers (c. 637 – 1171 CE)

The transition from Byzantine to Islamic rule in the 7th century CE initiated a period of profound political and economic realignment for the Afrin region. While daily life in the villages likely saw a high degree of continuity, the overarching administrative and economic structures that had supported their prosperity during the Classical apex were fundamentally altered. The era was characterized by the region's incorporation into successive Caliphates, the rise of a powerful local dynasty in Aleppo, and the violent instability brought by the Crusades. These shifts likely prompted a reorientation of the rural economy from export-driven monoculture to a more diversified system aimed at supplying a regional market, all while navigating the dangers of a contested frontier.

Continuity and Change under Islamic Rule

Following the decisive Battle of Yarmouk in 636 CE, the Muslim conquest of the Levant brought northern Syria, including the Afrin region, under the control of the Rashidun Caliphate. [25] The area was administratively incorporated into the

Jund Qinnasrīn , one of the military districts of Bilad al-Sham (Greater Syria), a structure that was maintained under the subsequent Umayyad Caliphate (661-750 CE). [3] The initial Arab conquest did not lead to a mass displacement of the local population or the founding of numerous new rural settlements. The conquering armies were relatively small, and their settlement was concentrated in existing urban centers and newly established garrison towns (

amsar ), none of which were founded in this part of Syria. [27] The existing rural landscape, with its established villages and largely Aramaic-speaking Christian populace, was left intact. The primary change was the imposition of a new ruling elite and a new system of taxation (

kharaj ), with agricultural production continuing much as before.

The overthrow of the Umayyads and the shift of the caliphal capital from Damascus to Baghdad under the Abbasids in 750 CE had significant consequences for Syria. The province was relegated to a peripheral status, losing its political centrality. [26] This political marginalization, combined with the disruption of the old Mediterranean trade networks that had been the backbone of the Byzantine economy, likely led to a gradual economic decline in Syria's rural hinterlands. The vast, imperial market for Afrin's olive oil would have contracted significantly, forcing a change in the economic basis of its villages.

This shift from a sea-oriented Byzantine imperial economy to a more insular, land-based caliphal system likely compelled a significant restructuring of the rural economy in the Afrin region. The decline in the mass export market for olive oil would have rendered the previous model of specialized monoculture unsustainable. In its place, villages would have been forced to diversify their agricultural output to meet their own subsistence needs and to supply the more limited, albeit still significant, regional market of Aleppo. This would have entailed a move towards a mixed agricultural model, cultivating grains, fruits, vegetables, and raising livestock alongside the still-important olive groves. This adaptation represents a transition from a highly specialized, prosperous cash-crop economy to a more resilient but perhaps less wealthy system of diversified farming, fundamentally altering land use patterns and the economic purpose of the region's settlements.

The Hamdanid Emirate of Aleppo (945-1004 CE)

As Abbasid central authority weakened in the 10th century, local dynasties emerged across the Islamic world. In northern Syria, the Arab Hamdanid dynasty established an independent emirate with its capital at Aleppo. [3] Under the rule of its most famous emir, Sayf al-Dawla, Aleppo became a brilliant political and cultural center, attracting renowned poets and philosophers. [29] For the villages of the Afrin region, the rise of a powerful and stable local court in Aleppo provided a new, secure market for their agricultural products. [29] This likely arrested the economic decline of the preceding centuries and provided a renewed impetus for rural production.

However, the Hamdanid period was also one of incessant warfare. Sayf al-Dawla was engaged in a near-constant struggle with the resurgent Byzantine Empire, which was pushing its frontiers back into northern Syria. [26] The Afrin region, situated directly on this volatile frontier, became a perpetual battleground. The Byzantine army under Nikephoros II Phokas sacked Aleppo itself in 962.29 This state of endemic conflict would have made rural life precarious. Villages in the exposed plains would have been highly vulnerable to raids and destruction, favoring settlement in more defensible highland locations within the Kurd-Dagh. The establishment of new villages would have been difficult, with the primary focus being on survival and fortification of existing settlements.

The Crusader Interlude (c. 1098-1124)

The geopolitical landscape was further complicated by the arrival of the First Crusade at the end of the 11th century. The establishment of the Crusader Principality of Antioch brought a new, aggressive power to the region's doorstep. [26] The Afrin area was briefly conquered by the Crusaders and became a contested frontier zone between them, the Seljuk Turks who had recently arrived from the east, and various local Muslim rulers. [5] This period intensified the military instability, with control of the region shifting frequently. Under such volatile conditions, the foundation of new, permanent agricultural settlements would have been exceptionally challenging, and the security of existing villages remained under constant threat. By this time, historical sources confirm that the Kurd Mountains were already recognized as being inhabited by Kurds, who were now caught in the midst of this multi-sided conflict. [3]

The Era of Military Elites: Ayyubid and Mamluk Dominance (c. 1171 – 1516 CE)

The Ayyubid and Mamluk periods represent a pivotal chapter in the history of Afrin's villages, marking a fundamental reorganization of the region's social, political, and economic landscape. The rise of the Kurdish-led Ayyubid dynasty created a new political context that likely favored Kurdish settlement and influence. More importantly, the widespread implementation and subsequent evolution of the iqta' system of military land tenure became the dominant factor in shaping rural life. This system directly tied the agricultural output of the villages to the maintenance of a new military elite, effectively militarizing the countryside and laying the groundwork for a new landed aristocracy that would persist for centuries.

The Ayyubid Ascendancy and Kurdish Influence

The Ayyubid dynasty, founded by the Kurdish sultan Salah al-Din (Saladin) in 1171, established its rule over Egypt and Syria, with major centers of power in Damascus and Aleppo. [34] The Ayyubid era was one of significant economic prosperity and cultural patronage. The rulers actively promoted Sunni Islam by constructing numerous madrasas (schools) and undertook major fortification and urban development projects, particularly in Aleppo, which flourished as a major commercial hub. [35]

The Ayyubid state was, at its core, a military enterprise led by a Kurdish family that relied heavily on a multi-ethnic army, in which Kurdish cavalry played a prominent role. [35] It is a reasonable conclusion that the dynasty would have favored its own ethnic kin in key military and administrative appointments. This political reality provides a strong context for an increase in the Kurdish presence and consolidation of Kurdish power in the strategic hinterland of Aleppo. The Kurd-Dagh, with its defensible terrain and proximity to the Ayyubid provincial capital, was an ideal location for the settlement of loyal military retainers.

The Iqta' System and the Rural Landscape

The primary instrument of Ayyubid and later Mamluk statecraft was the iqta' system, which they implemented throughout their Syrian domains. [26] The

iqta' was not a land grant in the sense of private ownership, but rather a grant of the right to collect the state's tax revenue from a designated parcel of land—typically one or more villages—in exchange for military service. [39] The holder of the grant, the

muqta' , was usually a military commander ( amir ). In lieu of a salary from the central treasury, he used the revenues from his iqta' to equip and maintain himself and a specified number of soldiers ( ajnad ), whom he was obligated to lead in battle at the sultan's command. [39]

This system had profound consequences for the villages of the Afrin region. It created a direct and formalized link between the agricultural surplus of a village and a specific unit of the Ayyubid army. The village became the economic engine that powered a segment of the military machine. The muqta' also bore responsibility for the economic well-being and development ( 'imara ) of his holding, which included maintaining infrastructure such as irrigation canals, as the productivity of the land directly determined his income and military capacity. [40] This system effectively placed the rural population under the direct authority of a military aristocracy.

The Ayyubid iqta' system was likely a key mechanism for the state-sponsored settlement of Kurdish military elites in the Kurd-Dagh. While Kurds were already present in the region, this period would have formalized and entrenched their position. Granting iqta's in the Kurd-Dagh to loyal Kurdish commanders served multiple strategic purposes: it rewarded followers, secured a critical frontier region, and placed a familiar and reliable population in charge of a strategic asset. This process would have transformed the Kurdish presence from a potentially pastoral or mercenary one into a landed, ruling class with legal and economic authority over the region's villages and their non-Kurdish inhabitants. It is highly probable that the name "Jabal al-Akrad" or "Kurd-Dagh" gained its definitive political and demographic significance during this era, reflecting not just the presence of Kurds, but their dominance as the region's military and administrative elite.

Consolidation under the Mamluks

The Mamluk Sultanate, a dynasty of former slave soldiers (primarily of Turkic and Circassian origin) who seized power from the Ayyubids in 1250, continued and refined the iqta' system. [42] After repelling the devastating Mongol invasion that had sacked Aleppo in 1260, the Mamluks restored stability to northern Syria and ruled the region until the Ottoman conquest in 1517.5 Under their rule, the state was the ultimate owner of most agricultural land (

miri ), which was systematically surveyed and distributed as temporary, non-hereditary iqta' grants through a highly centralized bureaucracy. [45]

A critical development during the later Mamluk period was the emergence of a method to circumvent the non-hereditary nature of the iqta' . Mamluk status and land grants could not be passed down to a commander's biological sons ( awlad al-nas ). [45] To secure their family's future, Mamluk

amirs increasingly used a legal mechanism to convert their state-granted holdings into inalienable religious endowments, or waqf . [45] By endowing the revenues of a village for a charitable purpose (such as a mosque or school) and appointing their own descendants as the perpetual administrators of the endowment, they could ensure that their family retained control over the land and its income for generations. This practice, which represented a de facto privatization of state land, became widespread.

This evolution from the temporary iqta' to the permanent waqf had long-term consequences for the social structure of the Afrin region. It facilitated the transition from a rotating military elite with temporary claims on villages to the establishment of a stable, hereditary, landed gentry. This process created powerful families with deep, multi-generational roots in the countryside and enduring control over specific villages and their resources. This new class of landed lords, whose power was based on quasi-permanent control of agricultural estates, laid the socio-economic foundation for the powerful, semi-autonomous tribal aghas and beys who are documented as dominating the region in the subsequent Ottoman period. [3] The

waqf system was the legal and economic bridge that connected the temporary military grant of the Mamluk state to the more permanent, feudal-like lordships of the Ottoman era.

Conclusion: A Synthesis of Settlement Dynamics in Kurd-Dagh

The history of the establishment of villages in the Afrin region before the 20th century is a complex narrative of continuity and transformation, shaped by the enduring influence of geography and the successive waves of imperial power, economic systems, and human migration. No single factor can account for the creation of its rural landscape. Instead, the evidence reveals a multi-layered process where the drivers of settlement evolved in response to changing historical circumstances. The region's history is a product of the interplay between geographic determinism, which provided the constant foundation for settlement; imperial integration, which amplified its economic potential; military imperatives, which shaped its strategic importance; and administrative systems of land tenure, which organized its social structure.

The fundamental constants in the region's settlement history are its geography and ecology. The fertile Afrin Valley, the reliable water sources, and the defensible highlands of the Kurd-Dagh provided a resilient foundation for agricultural life that persisted through millennia of political change. This is evidenced by the continuous occupation of key sites like Ain Dara from the Chalcolithic period onward.

Upon this foundation, two periods of radical transformation stand out. The first was the Late Roman-Byzantine era, when integration into the vast, secure, and commercially interconnected Mediterranean world fueled an economic boom based on olive oil production. This period of unprecedented prosperity led to a dense network of affluent agricultural villages, creating a landscape of intensive cultivation and rural wealth. The second major rupture occurred with the rise of the Ayyubid and Mamluk military elites. The implementation of the iqta' system fundamentally restructured the socio-economic fabric of the countryside, tying the villages directly to a military aristocracy. This system was likely the primary mechanism through which a Kurdish ruling class was formally established in the Kurd-Dagh, giving the region its lasting demographic and political character. The subsequent evolution of the iqta' into the hereditary waqf endowment created a stable, landed gentry, cementing the power of elite families over the rural landscape and setting the stage for the social structures of the Ottoman period.

The following table synthesizes the dominant factors that influenced the establishment and character of villages in the Afrin region across the major historical epochs preceding the French Mandate.

| Historical Period | Dominant Power | Primary Settlement Drivers | Secondary Drivers | Land Tenure System | Evidence of Kurdish Presence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neolithic-Iron Age (c. 6000-333 BCE) |

Local Kingdoms (e.g., Syro-Hittite) | Agriculture (subsistence), water access, defensible locations. | Religious centrality (e.g., Ain Dara), local trade routes. | Communal/Temple ownership. | None explicit; general Iranic/Indo-European migrations in wider region. |

| Hellenistic-Roman (c. 333 BCE-395 CE) |

Seleucid Empire, Roman Empire | Imperial military strategy (e.g., Cyrrhus), integration into provincial administration. | Road construction, supplying legions, urbanization in Antioch. | State land (ager publicus), private estates (latifundia). | Textual suggestion of settlement as mercenaries/archers. |

| Late Roman-Byzantine (c. 395-637 CE) |

Byzantine Empire | Export-oriented agriculture (olive oil boom), regional economic prosperity. | Religious pilgrimage, imperial security. | Private estates, imperial estates, church lands. | Established presence by the end of the period. |

| Early-Mid Islamic (c. 637-1171 CE) |

Rashidun, Umayyad, Abbasid Caliphates; Hamdanid Emirate | Agricultural production for regional markets (Aleppo), administrative continuity. | Frontier warfare with Byzantium, political fragmentation. | State tax land (kharaj), early forms of land grants. | Mentioned as established inhabitants by the Crusader period. |

| Ayyubid-Mamluk (c. 1171-1516 CE) |

Ayyubid Sultanate, Mamluk Sultanate | Military-feudal land grants (iqta') to support the army. | Economic patronage from Aleppo, post-Mongol reconstruction. | State-controlled iqta' system, evolving into private waqf endowments. | Strong inference of state-sponsored settlement of Kurdish military elites via the iqta' system. |

Works Cited

- Kurd Mountain - Wikipedia, accessed August 17, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kurd_Mountain

- The plain of Antioch and the Amuq Valley (Chapter Three) - Cambridge University Press, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/ancient-antioch/plain-of-antioch-and-the-amuq-valley/ED72CBEDA5CC45955FEFEF9B525E5CA8

- Afrin Region - Wikipedia, accessed August 17, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Afrin_Region

- Syria: Olive Cultivation on Hilly Land in the Northwestern Part of the ..., accessed August 17, 2025, https://satoyamainitiative.org/case_studies/syria-olive-cultivation-on-hilly-land-in-the-northwestern-part-of-the-country-and-along-its-mediterranean-coast/

- Afrin, Syria - Wikipedia, accessed August 17, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Afrin,_Syria

- CHALCOLITHIC SETTLEMENT PATTERNS IN SYRIA - Universidad de Granada, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.ugr.es/\~arqueologyterritorio/PDF12/2-Watfa.pdf

- Syrian qanat Romani: history, ecology, abandonment - Conflict Urbanism: Aleppo, accessed August 17, 2025, http://aleppo.c4sr.columbia.edu/seminar/Case-Studies/Water-as-a-War-Weapon/Syrian_Qanat_Romani.pdf

- The Euphrates States and Elbistan: Archaeology - Brill, accessed August 17, 2025, https://brill.com/display/book/edcoll/9789004349391/B9789004349391_s016.pdf

- Ain Dara (archaeological site) - Wikipedia, accessed August 17, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ain_Dara_(archaeological_site)

- Archaeology of the Rouj Basin: A Regional Study of the Transition from Village to City in Northwest Syria Vol. 1 - ResearchGate, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348482005_Archaeology_of_the_Rouj_Basin_A_Regional_Study_of_the_Transition_from_Village_to_City_in_Northwest_Syria_Vol_1

- The Early History of the Western Palmyra Desert region. The Change in the Settlement patterns and the Adaptation of subsistence Strategies to encroaching Aridity - OpenEdition Journals, accessed August 17, 2025, https://journals.openedition.org/syria/1496

- Exploring the lower settlements of Iron Age capitals in Anatolia and Syria | Antiquity, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antiquity/article/exploring-the-lower-settlements-of-iron-age-capitals-in-anatolia-and-syria/EE969C5E60D9772EB23687B81CB97660

- The Iron Age Settlement at ʻAin Dara, Syria: Survey and Soundings - Elizabeth Caecilia Stone, Paul E. Zimansky - Google Books, accessed August 17, 2025, https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Iron_Age_Settlement_at_%CA%BBAin_Dara_Sy.html?id=xgs-AQAAIAAJ

- Afrin, Syria - Wikiwand, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Afrin,_Syria

- Roman Syria - Wikipedia, accessed August 17, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Syria

- (PDF) S3 Fig - ResearchGate, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/306533099_S3_Fig

- Ancient villages of Northern Syria - World Heritage Site, accessed August 17, 2025, https://worldheritagesite.org/list/ancient-villages-of-northern-syria/

- Ancient villages, Syria - Med-O-Med, accessed August 17, 2025, https://medomed.org/featured_item/ancient-vilages-of-northern-syria-syrian/

- Trade and Transport in Late Roman Syria - ScholarWorks@UARK, accessed August 17, 2025, https://scholarworks.uark.edu/context/etd/article/3133/viewcontent/Fletcher_uark_0011O_12154.pdf

- Who are the Kurds ? - Institut kurde de Paris, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.institutkurde.org/en/info/who-are-the-kurds-s-1232550927

- en.wikipedia.org, accessed August 17, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Kurds#:\~:text=From%20Islamic%20conquest%20up%20until,and%20formed%20their%20own%20states.

- Limes Arabicus - Wikipedia, accessed August 17, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Limes_Arabicus

- Limes Arabicus and Saracen Foederati: The Roman-Byzantine Desert Frontier in Late Antiquity | Ballandalus, accessed August 17, 2025, https://ballandalus.wordpress.com/2015/04/19/limes-arabicus-and-saracen-foederati-the-roman-byzantine-desert-frontier-in-late-antiquity/

- Remote Sensing Roman and Byzantine Eastern Frontier Zone in Landscape: Case Studies from Syria and Turkey, accessed August 17, 2025, http://www.dl.edi-info.ir/Remote%20Sensing%20Roman%20and%20Byzantine%20Eastern%20Frontier%20Zone%20in%20Landscape.pdf

- Early Muslim conquests - Wikipedia, accessed August 17, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Early_Muslim_conquests

- Syria - Umayyad Dynasty, Damascus, Middle East | Britannica, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/place/Syria/The-Umayyads

- Early Islamic Settlement, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.brown.edu/Departments/Joukowsky_Institute/courses/islamiccivilizations/files/7195823.pdf

- Early Islamic Settlement, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.brown.edu/Departments/Joukowsky_Institute/courses/islamicarch2011/files/15355107.pdf

- Aleppo | History, Map, Citadel, Civil War, Population, & Facts - Britannica, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/place/Aleppo

- Hamdanid dynasty - Wikipedia, accessed August 17, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hamdanid_dynasty

- History of Aleppo, between Anatolia and Mesopotamia - Medio Oriente e Dintorni -, accessed August 17, 2025, https://mediorientedintorni.com/index.php/2020/07/08/aleppo-between-anatolia-and-mesopotamia/?lang=en

- The Byzantine conquest of Cilicia and the Hamdanids of Aleppo, 959-965 - ResearchGate, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291070390_The_Byzantine_conquest_of_Cilicia_and_the_Hamdanids_of_Aleppo_959-965

- Afrin Syria - The Kurdish Project, accessed August 17, 2025, https://thekurdishproject.org/kurdistan-map/syrian-kurdistan/afrin-syria/

- A Brief History of the Ayyubid Dynasty - Riwaya, accessed August 17, 2025, https://riwaya.co.uk/riwaya-blog/a-brief-history-of-the-ayyubid-dynasty/

- Ayyubid dynasty - Islamic History, accessed August 17, 2025, https://islamichistory.org/ayyubid-dynasty/

- Aleppo | Silk Roads Programme - UNESCO, accessed August 17, 2025, https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/content/aleppo

- Ancient City of Aleppo - UNESCO World Heritage Centre, accessed August 17, 2025, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/21/

- STATE AND CIVILIZATION UNDER THE SYRO-EGYPTIAN AYYUBIDS (1171-1250) ottor of piiilo^aplip - CORE, accessed August 17, 2025, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/144516393.pdf

- The Evolution of the Iqta' System under the - Mamluks-An Analysis of al-Rawk al-Husāmī and al-Rawk al-Nāṣirī, accessed August 17, 2025, https://toyo-bunko.repo.nii.ac.jp/record/3186/files/Memoirs37_05_SATO.pdf

- Untitled, accessed August 17, 2025, https://journals.ku.edu.kw/ajh/index.php/ajh/article/download/1317/751/6817

- THE IQT A' SYSTEM IN EGYPT AND SYRIA UNDER THE AYYUBIDS The amirs and high officials in Egypt had held the iqfa's since the Fati - Brill, accessed August 17, 2025, https://brill.com/display/book/9789004493186/B9789004493186_s008.pdf

- Mamluk | History, Significance, Leaders, & Decline | Britannica, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Mamluk-soldier

- Mamluk Sultanate - Wikipedia, accessed August 17, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mamluk_Sultanate

- Who Were the Mamluks? - History Today, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.historytoday.com/miscellanies/who-were-mamluks

- Mamluks, Property Rights, and Economic ... - Lisa Blaydes, accessed August 17, 2025, https://blaydes.people.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/sbiybj24621/files/media/file/land1.pdf

- Land tenure policies in the Near East, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.fao.org/4/y8999t/y8999t0f.htm

- The Political Economy (Chapter 5) - The Mamluk Sultanate - Cambridge University Press, accessed August 17, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/mamluk-sultanate/political-economy/70D92BF2A17F61D002E02CB8BA71D94F

- Popular responses to mamluk fiscal reforms in Syria - OpenEdition Journals, accessed August 17, 2025, https://journals.openedition.org/beo/60?lang=en

- History of the Kurds - The Kurdistan Memory Programme, accessed August 17, 2025, https://kurdistanmemoryprogramme.com/history-of-the-kurds/

- Al-Hasakah Governorate - Wikipedia, accessed August 17, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Al-Hasakah_Governorate

- KURDS | Washington Kurdish Institute, accessed August 17, 2025, https://dckurd.org/kurds/

- Archaeological survey at Balama Byzantine Castle in Pisidia (southwest Turkey): a preliminary report - publisherspanel.com, accessed August 17, 2025, https://publisherspanel.com/api/files/view/2689266.pdf