The Historiographical Problem of the Guti

The Guti, also referred to as Gutians or Guteans, emerge in the historical record of the ancient Near East as enigmatic and disruptive figures during the late third millennium BCE. [1] They are credited in traditional accounts with one of the most significant events of the era: the overthrow of the Akkadian Empire, the world's first multinational political entity founded by Sargon of Akkad. [3] Following this collapse, they established a dynasty that held sway over parts of Mesopotamia for a period estimated to be around a century, before being violently expelled, an event that heralded the great Sumerian Renaissance under the Third Dynasty of Ur. [5] After this dramatic, if brief, appearance on the world stage, they fade from history, leaving behind more questions than answers. [7]

The central challenge in any study of the Guti is the profound historiographical problem they present. The Guti left behind no known written language, no textual corpus, and no records of their own history, culture, or motivations. [3] Consequently, our entire understanding of them is filtered through the uniformly hostile lens of their literate adversaries: the Sumerians, Akkadians, and later Babylonians. [3] These sources, far from being objective chronicles, are deeply biased, portraying the Guti as the archetypal barbarian—uncivilized, impious, and wantonly destructive. [10]

This "barbarian" narrative is pervasive and visceral. Mesopotamian literary texts, composed largely after the Guti had been defeated, paint a lurid picture of a people who were a scourge upon the land. The famous literary composition, The Cursing of Agade , describes them as a divinely ordained punishment, an "unbridled people, with human intelligence but with the instincts of dogs and the appearance of monkeys". [3] They are blamed for bringing famine, disrupting trade, and neglecting the vital irrigation canals upon which Mesopotamian civilization depended. [12] Utu-hengal of Uruk, the king who eventually drove them out, describes them in his victory stele as the "fanged snake of the mountains". [6] This framing of the Guti as a subhuman, destructive force served a clear political and theological purpose for Mesopotamian scribes: it provided a simple, external explanation for the traumatic collapse of the mighty Akkadian Empire and legitimized the new dynasties that rose by claiming to have restored order from chaos.

This report seeks to deconstruct this hostile narrative and move beyond the caricature of the Guti. The objective is not to exonerate them, but to achieve a more nuanced and historically responsible understanding by critically examining the available evidence. The methodology employed will involve several key steps: first, a careful analysis of the limited direct evidence, primarily the list of Gutian king names and the few inscriptions commissioned by their rulers; second, a contextualization of the Gutian intervention within the broader political and environmental crises of the late third millennium BCE; third, a critical reading of the Mesopotamian sources themselves, treating them as literary and political documents rather than straightforward historical accounts; and finally, an evaluation of modern scholarly theories regarding Gutian origins and impact.

Ultimately, the study of the Guti becomes an exercise in historiography—an investigation into how history is written and for what purpose. They serve as a powerful case study in how a literate, urbanized civilization defines itself against an external "other." The historical Guti are buried beneath a literary archetype, a trope of the "barbarian at the gates" that was so potent it outlived the people it originally described, becoming a generic label for any threatening group emerging from the Zagros Mountains for centuries to come. [3] This report will endeavor to separate the historical people from the enduring myth.

The Land of Gutium

Geographical and Ethnolinguistic Origins

A. Geographical Homeland: The Zagros Mountains

The unanimous consensus of ancient sources places the homeland of the Guti, known as Gutium, in the Zagros Mountains. [1] This formidable mountain range forms a natural barrier between the alluvial plains of Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) and the vast Iranian Plateau. More specifically, cuneiform texts locate Gutium in the central Zagros, in a region corresponding to the vicinity of modern Hamadan in western Iran, situated to the north of the ancient kingdom of Elam. [3]

This region was far from an isolated or desolate wilderness. The Zagros served as a critical transit corridor for trade, migration, and military campaigns, connecting Mesopotamia with the resource-rich lands of the Iranian Plateau and Central Asia. [15] For the Mesopotamians, the mountains were a vital source of essential raw materials unavailable in the river valleys, including timber, stone, and, most importantly, metals like copper. [15] This made the Zagros a perennial focus of Mesopotamian foreign policy, alternating between trade and military conquest to secure access to its resources. The Guti, therefore, emerged not from a remote periphery but from a region of immense strategic and economic importance.

It is crucial, however, to recognize that "Gutium" was likely a fluid geographical concept rather than a precisely bordered nation-state. [14] The scholar Marc van de Mieroop has cautioned that the name was used in Mesopotamian records for over a millennium, and it is highly improbable that it always referred to the exact same region or the same group of people. [3] In the context of the late third millennium BCE, Gutium denoted the mountainous territory from which the people who overthrew Akkad originated.

B. The Enigma of the Gutian Language

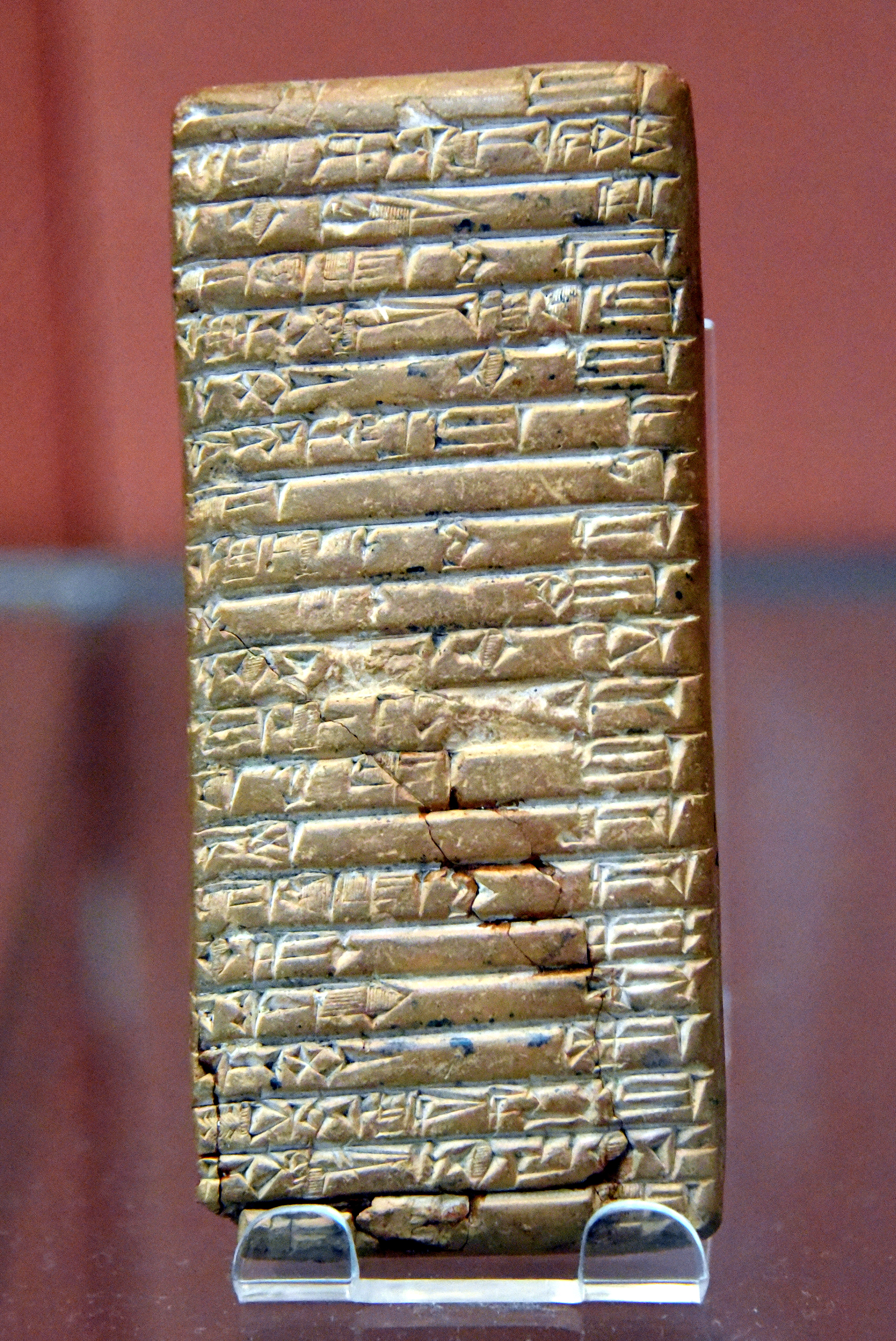

The Gutian language is one of history's great linguistic puzzles. It is officially designated as an unclassified, extinct language, meaning its genetic relationship to any known language family has not been established. [16] Its existence is confirmed by Mesopotamian administrative texts, such as a tablet from the city of Adab dating to the reign of the Akkadian king Shar-Kali-Sharri, which mentions the need for "an interpreter for the Gutean language". [14] This proves it was a distinct tongue, incomprehensible to Akkadian speakers.

The only direct, albeit meager, evidence of the language itself comes from a list of Gutian ruler names preserved in the Sumerian King List (SKL). [18] This document provides a sequence of approximately 21 kings with names like Inkishush, Sarlagab, Shulme, and Yarlaganda. [19] However, using this list for linguistic analysis is fraught with peril. The names were transcribed by Sumerian and Babylonian scribes, potentially altering their original phonology, and different manuscript copies of the SKL present variations in the names and their spellings, making any reconstruction highly unreliable. [18]

Despite these challenges, the tantalizing list has prompted several speculative theories. The most famous and controversial is the "Tocharian hypothesis," proposed in a posthumously published article by the scholar W.B. Henning. [18] He suggested a link between Gutian and the Tocharian languages, an extinct branch of the Indo-European family known from texts discovered in the Tarim Basin of Northwest China, dating from the 6th to 8th centuries CE. Henning based his argument on several points: the endings of some Gutian king names resembled case endings in Tocharian; the name

Guti was phonologically similar to Kuči , the native name of the major Tocharian city of Kucha; and a land named Tukriš , mentioned alongside Gutium in a Mesopotamian inscription, could be related to twγry , a name believed to refer to the Tocharians. [18] However, this theory has been rejected by most scholars. The immense chronological gap of over two millennia and the vast geographical distance separating the Guti from the known Tocharians, combined with the scantiness of the linguistic data, render the connection too speculative to be widely accepted. [18]

Other theories have been proposed, including attempts to link the Gutian king names to Turkic languages, a view popular in some nationalist scholarship but which lacks broad support in mainstream Assyriology. [4] Given the state of the evidence, the most intellectually sound position remains that Gutian is an unclassified language isolate, its secrets likely lost to time.

C. Theories of Ethnic Origin

The mystery of the Gutian language is mirrored in the uncertainty surrounding their ethnic identity. The Indo-European hypothesis, often tied to Henning's linguistic theory, suggests the Guti were an early wave of Indo-European migrants who entered the Near East via the Caucasus. [21] Some proponents of this view imagine a mixed population, with a chariot-wielding Indo-European military elite ruling over a majority of indigenous Zagros peoples. [21] Tenuous support for this is sometimes drawn from later traditions or interpretations that describe the Guti as phenotypically different, possibly "blonde" or "pale-skinned," though such evidence is extremely weak and anachronistic. [24]

A more conservative and widely accepted hypothesis posits that the Guti were simply an indigenous people of the Zagros region. [25] They would have been part of a larger tapestry of non-Sumerian, non-Semitic mountain peoples who periodically interacted with Mesopotamia, a group that included other peoples like the Lullubi and, later, the Kassites. [10] In this view, the Guti were not foreign invaders from a distant land but a local power that grew to prominence.

In modern times, some nationalist historiographies have sought to claim the Guti as direct ancestors of the Kurdish people. [7] This claim is primarily based on the geographical coincidence that the ancient land of Gutium overlaps with parts of modern Kurdistan. However, this connection is rejected by mainstream scholarship as speculative and politically motivated. There is no demonstrable linguistic, cultural, or textual continuity that bridges the millennia between the disappearance of the Guti and the emergence of a distinct Kurdish identity. [7]

The quest to define the Guti's ethnic and linguistic identity ultimately reveals the limits of our knowledge. The available data is so poor that it can be molded to support various theories, none of which can be definitively proven. Their most certain characteristic, from the Mesopotamian perspective, was their profound "otherness." Attempting to force them into a known ancient or modern category may be anachronistic. It is perhaps most accurate to see them as a distinct Zagros people whose specific affiliations are, for now, unrecoverable.

The Fall of Akkad

Gutian Invasion or Systemic Collapse?

A. The Traditional Narrative: The Guti as Destroyers

The traditional Mesopotamian account of the fall of the Akkadian Empire is one of sudden, catastrophic violence inflicted by an external enemy. In this narrative, the Guti are cast as the sole agents of destruction, sweeping down from their mountain homeland to lay waste to the civilized world. [3] They are said to have sacked and destroyed the imperial capital of Agade—a city so thoroughly ruined that its location remains unknown to this day—and plunged the land into a dark age of chaos and famine. [13] This powerful and simple explanation, blaming a barbarian invasion for the collapse of a great empire, became the canonical version of events, repeated in Mesopotamian literature for centuries.

B. The Akkadian Empire on the Brink: Internal Decay

A closer examination of the evidence from the late Akkadian period reveals a far more complex picture. The empire was already showing signs of severe internal stress long before the Gutian takeover. The reign of Naram-Sin's son, Shar-Kali-Sharri (c. 2217-2193 BCE), was marked by constant struggles to maintain control over the vast territory. [3] His death precipitated a full-blown political crisis. The Sumerian King List captures this moment of anarchy with a famous rhetorical question: "Then who was king? Who was not king?" It proceeds to list four different kings—Irgigi, Nanum, Imi, and Elulu—all ruling in a span of just three years (c. 2193-2190 BCE). [20] This entry is a clear testament to a period of intense internal power struggles, civil war, and the complete breakdown of centralized authority. [28]

Furthermore, the Guti were not a sudden, unknown threat. Their presence in Mesopotamia was a gradual development. They had been filtering into the empire as settlers, pastoralists, and likely mercenaries for a generation or more. [14] The administrative text from Adab that mentions a Gutian-language interpreter during Shar-Kali-Sharri's reign is crucial evidence of this established, and at times peaceful, presence within the empire's borders. [14] The Gutian rise to power was therefore not a single, unforeseen invasion, but the culmination of a long-term process of migration and infiltration into a progressively weakening state.

C. The 4. [2] -Kiloyear Event: Climate as a Catalyst

Compounding the political instability was a catastrophic environmental factor. A growing body of paleoclimatological and archaeological evidence points to a severe, abrupt, and prolonged climate change episode around 2200 BCE, now widely known as the 4. [2] -kiloyear event. [29] This event is associated with a dramatic shift to a much drier climate across the Near East and other parts of the world.

For the Akkadian Empire, the consequences would have been devastating. The empire's agricultural heartland, particularly the rain-fed plains of northern Mesopotamia, would have suffered a catastrophic collapse due to persistent drought. [13] This would have triggered a cascade of crises: widespread famine, the abandonment of northern cities and a surge of climate refugees moving south, the loss of agricultural surpluses that were the foundation of the state's economy, and intensified conflict between settled farmers and nomadic pastoralists over dwindling water and grazing resources. [8] This environmental crisis severely eroded the social and economic foundations of the Akkadian state, leaving it critically vulnerable.

D. Synthesis: A Multifactorial Collapse

The fall of the Akkadian Empire was not a single event caused by a single actor. It was a systemic collapse driven by a fatal convergence of internal political decay, long-term environmental degradation, and external pressure. [30] The Guti should not be seen as the primary cause of the collapse, but rather as an opportunistic force that exploited a pre-existing power vacuum. [8] They were both a symptom of Akkad's weakness and an accelerant of its final demise. The traditional "barbarian invasion" narrative, while politically useful for later Mesopotamian dynasties, obscures this more complex and sobering reality of a great empire crumbling under the combined weight of internal strife and climate change. The Guti were simply the ones who delivered the final blow to a structure that was already hollowed out from within.

The Gutian Dynasty

A Century of Mesopotamian Disunity (c. 2154–2050 BCE)

The period following the collapse of Akkad, often termed the Gutian Period (c. 2218-2047 BCE in some chronologies 32), is portrayed in Mesopotamian sources as a chaotic interregnum. However, a critical analysis of the available evidence suggests a more complex reality of political adaptation, internal instability, and regional fragmentation rather than a monolithic "dark age."

A. The Nature of Gutian Governance: Chaos or Adaptation?

The official narrative, penned by the Sumerian and Babylonian scribes who came after, is one of unmitigated disaster. Gutian rule is described as incompetent and uncivilized, characterized by the neglect of the vital irrigation canal networks, the disruption of trade, and a general decline in prosperity and public safety. [13] Later texts, like the Weidner Chronicle, depict the Gutian kings as impious and "unaware how to revere the gods, ignorant of the right cultic practices". [6] This portrayal served to contrast the "illegitimate" rule of the foreign Gutians with the "legitimate" order restored by the subsequent Sumerian kings.

This uniformly negative depiction, however, is challenged by evidence that the Gutian rulers attempted to adapt to and participate in the established traditions of Mesopotamian kingship. They did not rule from mountain strongholds but established their capital in the long-standing Sumerian city of Adab. [34] More significantly, at least one Gutian king, Erridu-pizir, is known from his own royal inscriptions found in the holy city of Nippur. [10] In these texts, written in Old Akkadian cuneiform, he adopts the prestigious title of the great Akkadian kings: "King of Gutium, King of the Four Quarters". [6] This was a clear and deliberate act of political legitimization, an attempt to cast himself as a successor to the Akkadian dynasty, not merely a foreign marauder. The fact that Erridu-pizir is not even mentioned in the Sumerian King List underscores the incompleteness and biased nature of our primary textual source for the period. [10] The use of cuneiform for these inscriptions also refutes the simplistic notion that the Gutians were universally illiterate; while they may have lacked their own script, their elite utilized the scribal infrastructure of the land they now controlled. [12]

B. The Sumerian King List and Political Instability

The Sumerian King List (SKL) remains the principal, albeit problematic, source for the chronology of the Gutian dynasty. It lists approximately 21 kings who ruled over a period of roughly 91 years. [19] The SKL's entry for the dynasty begins with a fascinating and revealing statement: "In the army of Gutium, at first no king was famous; they were their own kings and ruled thus for 3 years". [33] This suggests that the Guti may have initially been led by a council of chiefs or some form of collective leadership, and only adopted the Mesopotamian model of hereditary, singular kingship after consolidating their power.

The most striking feature of the list is the remarkably short reigns of most of the kings. Many ruled for six years or fewer, with several reigning for only one or two years. [19] This pattern strongly indicates a state of chronic political instability, likely fueled by intense infighting and succession struggles among rival Gutian clans or leaders. [3] They were unable to establish the kind of stable, dynastic succession that characterized the great Mesopotamian empires.

The following table synthesizes the list of Gutian kings from various sources, highlighting the inconsistencies in names and reign lengths that typify the fragmentary nature of the evidence.

- Erridu-pizir

- Nameless King / Imta / Nibia

- Inkishush / Ingišu

- Sarlagab / Ikukum-la-qaba

- Shulme / Šulme

- Elulmesh / Silulumeš

- Inimabakesh / Inimabakeš

- Igeshaush / Ige'a'uš

- Yarlagab / I'ar-la-qaba

- Ibate

- Yarlangab / Yarla

- Kurum

- Apil-kin / Habilkin

- La-erabum / Lasirab

- Irarum

- Ibranum

- Hablum

- Puzur-Suen / Puzur-Sin

- Yarlaganda

- Si-um / Si'um

- Tirigan

Erridu-pizir

Reign: 3 years (per inscription)

Reigned for 3 years (per inscription). Yes 10 attested outside SKL.

Nameless King / Imta / Nibia

Reign: 3 years

Reigned for 3 years. No 19 attested outside SKL.

Inkishush / Ingišu

Reign: 6 or 7 years

Reigned for 6 or 7 years. No 19 attested outside SKL.

Sarlagab / Ikukum-la-qaba

Reign: 6 or 1 years

Reigned for 6 or 1 years. Possibly 18 attested outside SKL.

Shulme / Šulme

Reign: 6 years

Reigned for 6 years. No 19 attested outside SKL.

Elulmesh / Silulumeš

Reign: 6 years

Reigned for 6 years. No 19 attested outside SKL.

Inimabakesh / Inimabakeš

Reign: 5 years

Reigned for 5 years. No 19 attested outside SKL.

Igeshaush / Ige'a'uš

Reign: 6 years

Reigned for 6 years. No 19 attested outside SKL.

Yarlagab / I'ar-la-qaba

Reign: 15 or 3 years

Reigned for 15 or 3 years. No 19 attested outside SKL.

Ibate

Reign: 3 years

Reigned for 3 years. No 19 attested outside SKL.

Yarlangab / Yarla

Reign: 3 years

Reigned for 3 years. No 19 attested outside SKL.

Kurum

Reign: 1 year

Reigned for 1 year. No 19 attested outside SKL.

Apil-kin / Habilkin

Reign: 3 years

Reigned for 3 years. No 19 attested outside SKL.

La-erabum / Lasirab

Reign: 2 years

Reigned for 2 years. Yes (seal inscription) 19 attested outside SKL.

Irarum

Reign: 2 years

Reigned for 2 years. No 19 attested outside SKL.

Ibranum

Reign: 1 year

Reigned for 1 year. No 19 attested outside SKL.

Hablum

Reign: 2 years

Reigned for 2 years. No 19 attested outside SKL.

Puzur-Suen / Puzur-Sin

Reign: 7 years

Reigned for 7 years. No 19 attested outside SKL.

Yarlaganda

Reign: 7 years

Reigned for 7 years. Yes (inscription) 19 attested outside SKL.

Si-um / Si'um

Reign: 7 years

Reigned for 7 years. Yes (inscription) 19 attested outside SKL.

Tirigan

Reign: 40 days

Reigned for 40 days. Yes (Utu-hengal stele) 19 attested outside SKL.

Voices from the "Dark Age"

Gudea of Lagash and the Persistence of Sumerian Culture

The single most compelling counter-argument to the narrative of a universal "dark age" under Gutian rule comes from the southern Sumerian city-state of Lagash. While the Gutians dominated the north, Lagash, under the leadership of its pious and energetic ruler ( ensi ) Gudea (c. 2144-2124 BCE), experienced a remarkable period of peace, prosperity, and cultural florescence. [40]

A. Gudea's Principality: An Oasis of Stability

The extensive inscriptions left by Gudea reveal a ruler whose priorities were not military conquest but piety, social justice, and monumental construction. [42] He consciously adopted the traditional Sumerian ideal of the "Shepherd King," casting himself as a humble servant of his city's patron deity, Ningirsu, and a caretaker for his people. [44] His texts speak of reforms, such as ensuring justice for orphans and widows and creating a period of social harmony where "no mother shouted at her child" and masters did not strike their slaves. [42]

This internal stability was matched by external reach. Gudea's inscriptions boast of extensive trade networks that brought precious materials to Lagash from distant lands. These included cedar wood from the Amanus mountains of Syria and Lebanon, diorite for his famous statues from Magan (likely modern Oman), and gold and copper from other regions. [39] The ability to organize and protect such long-distance trade expeditions demonstrates that Lagash was a stable and wealthy state with significant political autonomy, capable of projecting economic power far beyond its borders. [12]

B. A Flourishing of Art and Piety

Gudea's reign is rightly considered a golden age of Neo-Sumerian art and architecture. [41] Archaeologists have recovered more than two dozen masterfully carved statues of Gudea, typically made from hard, imported diorite. These statues, with their serene expressions and powerful forms, represent a high point of Sumerian artistic achievement. [42]

Gudea's greatest legacy was his vast program of temple construction. He is credited with building or restoring at least fifteen temples, but his crowning achievement was the rebuilding of the Eninnu, the great temple of the god Ningirsu. [43] This massive undertaking is described in meticulous detail on two large clay cylinders (Gudea Cylinders A and B), which are among the longest and most important works of Sumerian literature ever discovered. [42] Such a project would have required immense resources, a highly organized labor force, and a period of sustained peace—all conditions that starkly contradict the image of a land universally plunged into poverty and chaos.

C. Gudea and the Gutians: A Relationship of Pragmatism

The prosperity of Lagash during the Gutian period points to a pragmatic, if unstated, political accommodation. Gudea's inscriptions detail his military preparations and campaigns against Elam to the east, but they are silent on any conflict with the Gutians to the north. [12] This suggests that Gudea pursued a policy of careful diplomacy and military deterrence. He likely secured the independence of Lagash by acknowledging the nominal overlordship of the Gutians, perhaps through the payment of tribute, while simultaneously building up his city's defenses to make any potential attack too costly. [42]

The case of Gudea of Lagash fundamentally reshapes our understanding of the Gutian period. It demonstrates that Mesopotamian civilization did not collapse. Rather, with the demise of a centralized imperial authority, political power became fragmented. While the old Akkadian heartland may have suffered under direct Gutian administration, this decentralization created opportunities for well-positioned and well-led city-states like Lagash to reassert their independence and flourish. The "dark age" was not a universal cultural eclipse, but a complex period of political realignment with diverse local outcomes.

The Sumerian Renaissance

Utu-hengal's Campaign and the Expulsion of the Guti

The period of Gutian dominance in Mesopotamia came to a decisive end through a resurgence of native Sumerian power, a movement that culminated in the establishment of the great Third Dynasty of Ur. This "Sumerian Renaissance" was initiated by a king from the ancient city of Uruk.

A. The Rise of Uruk and Utu-hengal

Toward the end of the 21st century BCE, the city of Uruk re-emerged as a major political force under its king, Utu-hengal (reigned c. 2055–2048 BCE). [5] He positioned himself as the leader of a Sumerian liberation movement. In his royal inscriptions, Utu-hengal is portrayed as a divinely chosen champion, entrusted by the chief god of the Sumerian pantheon, Enlil, with the sacred mission to "wipe out the name of Gutium" and restore the kingship of Sumer to its rightful place. [46]

B. The Defeat of Tirigan: History and Propaganda

The primary source detailing the expulsion of the Guti is the Victory Stele of Utu-hengal, a monumental inscription of which a later copy survives. [6] The text is a masterpiece of royal propaganda, providing a dramatic, stage-managed narrative of the campaign. It begins by vilifying the enemy, describing Gutium as "the fanged snake of the mountains" that "filled Sumer with wickedness". [47] Utu-hengal then prays to the gods for support, rallies the citizens of Uruk and Kulaba "as one man," and marches out to confront the Gutian forces. [47]

According to the stele, the campaign was swift and decisive. Utu-hengal first captured two of the Gutian king's generals who had been sent as envoys. [47] He then engaged and defeated the main Gutian army. The last king of the Gutian dynasty, Tirigan—who had been on the throne for a mere 40 days, a testament to the Gutians' own terminal instability—"ran away alone on foot". [47] He sought refuge in the town of Dabrum, but its inhabitants, knowing that Utu-hengal was now the dominant power, seized Tirigan and his family and handed them over to the king of Uruk. [46] The inscription culminates with the ultimate act of subjugation: "Before the god Utu, Utu-hengal made him lie at his feet and placed his foot on his neck". [47]

While recording a historical event, the stele's primary purpose was ideological. By framing the conflict as a holy war sanctioned by Enlil, dehumanizing the enemy, and magnifying the king's personal heroism, the inscription served to legitimize Utu-hengal's seizure of power and his claim to be the rightful ruler of all Sumer. [6] The apparent ease of the victory may be a propagandistic exaggeration, as other sources suggest the Gutians were already weakened by pressure from Elam to the east, making them a less formidable opponent than the stele portrays. [50]

C. The Foundation of the Third Dynasty of Ur

Utu-hengal's reign as the sole king of a liberated Sumer was brief. After about seven years, he died in a tragic accident while inspecting a dam, and kingship passed to his most powerful subordinate, Ur-Nammu, who had been serving as the governor of Ur. [34]

Ur-Nammu (c. 2047–2030 BCE) and his successors founded the Third Dynasty of Ur (Ur III), which would become one of the most centralized and bureaucratic states in Mesopotamian history. [32] The new dynasty built directly upon the ideological foundation laid by Utu-hengal. Ur-Nammu and his formidable son, Shulgi of Ur, continued the war against the Guti, not just expelling them from the lowlands but launching punitive campaigns into their Zagros homeland, with one of Ur-Nammu's year names recording the "year Gutium was destroyed". [3] The military defeat of the Guti was thus the foundational act of the Neo-Sumerian Empire, a victory that was endlessly commemorated to unify the Sumerian cities under the new leadership of Ur and to justify its imperial authority as the restorers of civilization, order, and divine favor.

Legacy and Afterlife

The "Gutian" as a Mesopotamian Trope

The most enduring legacy of the Guti was not their century of rule, but the powerful and lasting idea of the "Gutian" that they bequeathed to the Mesopotamian cultural imagination. Long after they vanished as a distinct people, their name was transformed into a potent historical and literary trope.

A. The Barbarian Archetype in Mesopotamian Literature

The Guti's negative reputation was codified and immortalized in Mesopotamian literature, most notably in works composed during the Ur III period that followed their expulsion. The most influential of these is The Cursing of Agade . [51] This text is a work of theological history, a lament that retroactively explains the fall of the Akkadian Empire not as a result of complex political or environmental factors, but as divine retribution for the impiety of King Naram-Sin, who allegedly desecrated the temple of the god Enlil. [52] In this drama, the Guti are cast as the literal instrument of the gods' wrath, a mindless, destructive force unleashed upon the land. [3] This literary masterpiece cemented the image of the Guti in the Mesopotamian psyche as the ultimate symbol of the uncivilized "other," a cautionary tale about the consequences of offending the gods. Other works of the

naru literature genre, such as The Legend of Cutha , feature similar monstrous, mountain-dwelling creatures that echo the themes of barbarism indelibly associated with the Guti. [3]

B. "Gutian" as a Pejorative and Geographical Label

As a result of this powerful literary tradition, the term "Gutian" was detached from the specific historical people and evolved into a generic, and invariably pejorative, label. [4] For the next thousand years, Assyrian and Babylonian scribes used "Gutian" or "Gutium" to refer to any hostile or "uncivilized" group inhabiting the Zagros Mountains to the northeast. [3] The term was applied to entirely different peoples with no ethnic or linguistic connection to the original Guti, including the Kassites, the Lullubi, and, most frequently in later Assyrian texts, the Medes and other Iranian populations. [3] "Gutium" ceased to be a specific place and became a geographical shorthand for the dangerous, chaotic, and barbaric mountain periphery that perpetually threatened the ordered world of the Mesopotamian plains. [4]

C. The Disappearance of the Guti

After their defeat by Utu-hengal and the subsequent punitive campaigns by the kings of Ur, the Guti as a distinct political and ethnic entity effectively vanish from the historical record. [7] Their ultimate fate is unknown. They were likely either militarily shattered and assimilated into the other populations of the populous Zagros region, or their name simply fell out of use as a specific identifier, having been completely supplanted by its new, generic meaning. As discussed previously, modern attempts to forge a direct line of descent from the ancient Guti to contemporary ethnic groups like the Kurds remain entirely speculative, lacking the necessary linguistic, archaeological, or textual evidence to be considered historically viable. [7]

The historical Guti were thus overwritten by their own legacy. They became a concept, a cautionary tale, and a flexible label for the "barbarian at the gates." This idea proved to be far more influential and long-lasting than their actual historical kingdom.